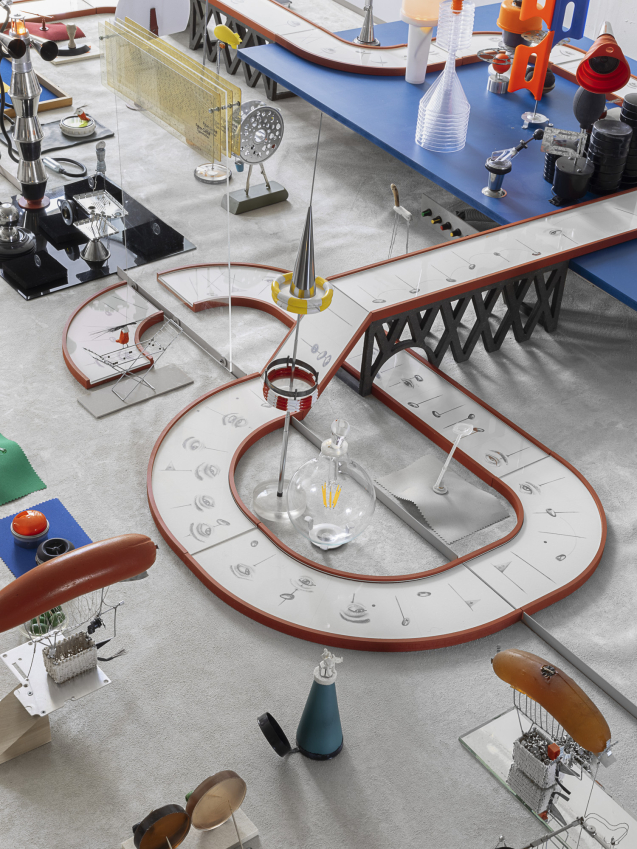

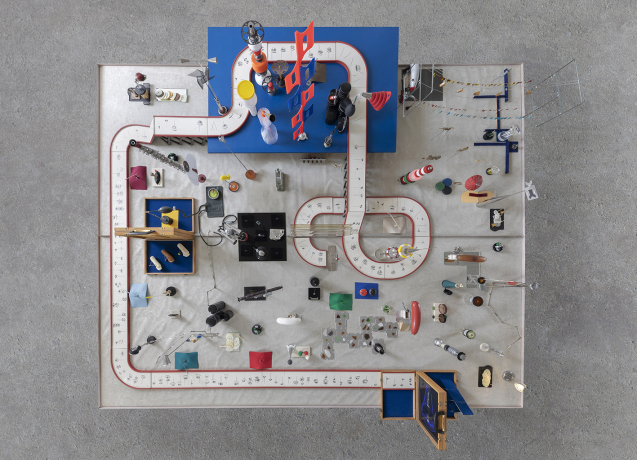

Glasses clink, eye meets eye, hands are extended to be shaken. In “Finger Food and Future Mistakes,” Guy Goldstein brings together two different events—the multi-participant World’s Fair and a small, intimate home cocktail—for a shared inquiry into the forces that drive them and the motivations that set them in motion. From bottles opened for an intimate toast to the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, from a face to face conversation to an outdoor public address system, from the demand not to crowd to the yearning to be part of a crowd. The exhibition delves into the basic need for a human encounter and the places where it bends or adapts itself to the human need for organization, supervision, and maintaining norms. The desire to predict the future goes hand in hand with the need to test and check, and the knowledge of everything that has happened, is happening, and is supposed to happen.

The world’s fairs, which began in the mid-19th century, were a grand celebration of tourism and commerce, the spearhead of scientific, commercial, technological, and artistic inventions and innovations: a huge carnival, embedding monumental architecture along with political and economic considerations, spiced with dreams and curiosity about the future of humanity. The great inventions, the innovative buildings, the exciting promises, were all presented for the first time at the fair—from ketchup to the fluorescent light bulb, from the phone call to the zipper, from the television broadcast, the ice cream cone, the X-ray machine, and the Ferris wheel to Paris’s Eiffel Tower, Seattle’s Space Needle, London’s Crystal Palace, and other icons built especially for the fair. The cities were decorated for the festive event. Phallic structures were erected, and often removed too, in the blink of an eye. The world felt better, if only momentarily.

In April 1939, the New York World’s Fair opened under the title “The World of Tomorrow.” Amid monumental buildings and hovering dirigibles, between pavilions showcasing innovations and inventions from all over the world, crowds of visitors walked around wearing “I Have Seen the Future” pins, which corresponded with the fair’s slogan, promising a glimpse into the “Dawn of a New Day.”

That future, imagined throughout most of the 20th century, is now here. We know it well from movies and books: flying cars, control rooms full of screens...