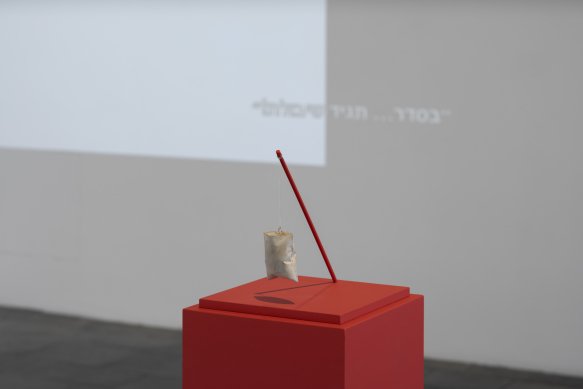

And the Gileadites took the passages of Jordan before the Ephraimites: and it was so, that when those Ephraimites which were escaped said, Let me go over; that the men of Gilead said unto him, Art thou an Ephraimite? If he said, Nay; Then said they unto him, Say now Shibboleth: and he said Sibboleth: for he could not frame to pronounce it right. Then they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan. [Judges 12: 5–6]

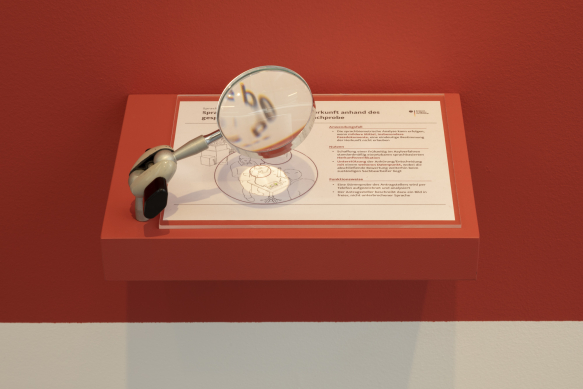

Loose lips sink ships. So do the palate and the tongue. The way we move the different parts that make up our mouth, the way the air passes through the throat, the way we pronounce certain letters and words and put together sentences, the way we activate the hundred muscles required to produce a sound—is essential to our identity. But more than that, it is fundamental to the way in which others understand, hear, and judge us.

In biblical times, it was the word shibboleth (swirl), whose pronunciation sealed fates. The Ephraimites, who tried to escape back to their land during a war, pronounced this word with an S sound rather than SH. The Gileadites, who needed a ruse to identify them, ordered everyone who took the passages of Jordan to say the word shibboleth aloud. The men of Ephraim, who pronounced this word as sibboleth, were thus identified, captured, and thrown into the stormy waters.

In the 13th century, during the Sicilian revolution on the outskirts of Palermo, the local word for chickpeas – ciceri – was used as a test to identify the French conqueror who was hiding in the city. In World War II, the Dutch underground used the district name “Scheveningen” to identify German spies, and the way the letter H is pronounced was used during the Irish Civil War to distinguish between Protestants and Catholics. Now, Ukrainian soldiers use the word palyanitsya, the name of a traditional Ukrainian bread, to identify Russian soldiers posing as Ukrainians...

Read more